Published in: Michael Cremo (2010) The Forbidden Archeologist, Bhaktivedanta Book Publishing, Los Angeles, pp. 215—219. Originally published in Atlantis Rising magazine in 2008.

My main interest is archeological evidence for extreme human antiquity. But I am also interested in other questions. One of them is the history of the Vedic culture in India. By Vedic culture, I mean the culture based on the Vedas, the original Sanskrit books of knowledge, and the books derived from them. The current opinion among mainstream scholars is that Vedic culture came into the Indian subcontinent around 3,500 years ago, from the northwest. But the traditional opinion among followers of Vedic culture is that it has always been present in the Indian subcontinent. In this article, I want to consider some archeological evidence that favors the latter point of view. It appears that ancient urban centers in the India subcontinent, which are more than 3,500 years old, show signs they were designed according to a Vedic system of architecture called vastu.

One of the earliest mentions of this system of architecture is found in the Sanskrit epic Mahabharata, which according to the text itself was composed about five thousand years ago in India (modern secular scholars give it an age of three thousand years). Vastu can be used in the construction in individual structures, but it is also used for urban design. A main element of vastu is the concept of the vastu purusha, the personal form of vastu. There are various accounts of the origin of the vastu purusha. One goes like this: At the beginning of creation, there was an asura (demon) who opposed the demigods. The demigods led by Brahma pushed the demon down onto the earth’s surface, and the demigods took their places on his form to hold him there. Brahma named the demon vastu purusha. Offering the vastu purusha a kind of redemption, Brahma ordained that anyone building any kind of residence would have to pacify him with sacrifice and worship.

The form of the vastu purusha is depicted graphically in the vastu purusha mandala. The mandala, or diagram, is square. The square form represents the divine order whereas the circle represents unordered material reality. The purusha is depicted as a male, lying face down. The head occupies the northeast part of the mandala, and the feet are in the southwest. The right knee and right elbow meet in the southeast corner. The left knee and left elbow meet in the northwest corner. The form of the vastu purusha is thus contorted to fit in the confines of the square. The main square of the mandala is divided into 64 (8 x 8) or 81 (9 x 9) squares. Each square is inhabited by a demigod, each one taking its place on the form of the body of the vastu purusha.

Vastu and City Design

The first step in the construction of a new town is to level the ground. After the site is leveled, the vastu purusha mandala is drawn upon it, and this forms the basis for the design. A very common form of this mandala is the square. Many Indian cities, like Jaipur, show signs of vastu design.

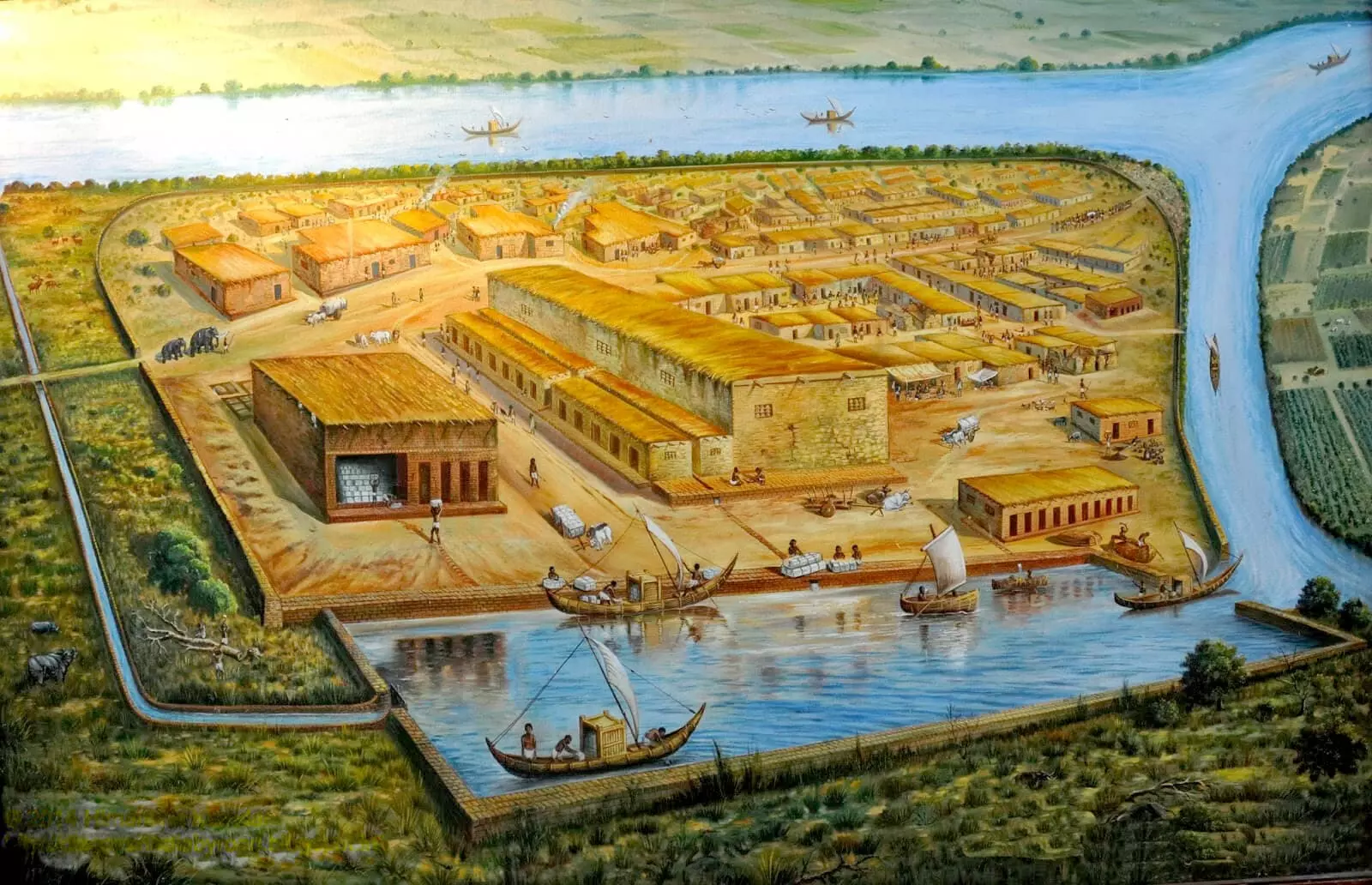

Over the past century, many ancient towns have been excavated in India, dating to four or five thousand years ago. The most famous of them are in the Indus Valley region (now part of Pakistan), including Mohenjo Dharo and Harappa. The latter site is generally used by scholars for the whole culture that produced these towns (the Harappan). Scholars have different opinions about the exact nature of the culture. Some say the culture was Vedic, the culture of the majority of Indians today. Others say that the culture was not Vedic, and that the people of Vedic culture entered India in much later times, no earlier than about 3,500 years ago. One problem is that the script of the Harappan culture has not been deciphered to the satisfaction of all scholars. Some have proposed Vedic decipherments and others have proposed non-Vedic decipherments. While this matter continues to be debated (I myself support a Vedic decipherment in principle), it may be useful to look for archeological evidence about the nature of the culture. In the spring of 2008, I went to India to investigate the design of the “Harappan” city of Lothal in Gujarat, India, which dates to the 3rd millennium BCE, to determine whether or not the design conforms to vastu principles. The answer to this question has implications for our understanding of the people who built Lothal. If the city was designed according to vastu principles, that would signify it is likely the people were part of the Vedic culture.

At Lothal, I looked at the site and the site plan for Period A, which goes back as far as 4,400 years ago, supposedly 1,000 years before people of Vedic culture entered India. The plan shows that Lothal was laid out in square form, with sides oriented to the cardinal directions. This corresponds to one of the standard vastu grids. According to vastu principles, an ideal site for a town is higher in the west and south than in the north and east. At Lothal, there is a definite elevation in the south, sloping down to the north and east. Experts in vastu say that houses facing the cardinal directions (north, south, east, west) are good, while those facing the corner points are exposed to evil influences. At Lothal, all the buildings face the main directions. Roads are oriented north to south, and east to west, another feature of vastu town design. According to vastu texts, waste water should drain to the north or east. I found that the main water drainage system at Lothal, in the area of the citadel, did drain to the east, as also noted in the site report.

According to vastu principles, the four social classes (workers, merchants, rulers, and priests) should occupy the western, southern, eastern, and northern sides of a town respectively. Workshops are found primarily on the western side of Lothal. The southeastern corner, Lothal’s center of trade, is occupied by a structure identified as a warehouse. The site plan shows the acropolis, identified as the residence of the town’s rulers (kshatriyas), extending from the central part of the site to the site’s eastern side. In the middle of the northern boundary of Lothal is a structure identified as a public fire altar, which would likely have been attended by priests (brahmanas). So the structures identified with the four classes seem to be located in the appropriate directions. The principal deity of the northern side of the vastu purusha mandala is Soma, the moon, and the quarter over which the moon rules is known as the “quarter of men.” The Lower Town of Lothal, which includes most of the residences, is in the northern half of the site, whereas the southern half of the town is occupied by the warehouse trade area, acropolis government area, and the workshop areas.

The Lothal site plan shows a cemetery outside the northwestern boundary wall, and S. R. Rao, the archeologist who excavated the site, said that the number of skeletons found there is quite small for a town the size of Lothal. He estimated the population at fifteen thousand. So he considered it likely that cremation was the most common form of dealing with dead bodies. The deity of the northwest corner of the 81-square vastu purusha mandala is Roga, disease; just below Roga is Papayakshman, consumption; and just below Papayakshman is Shosha, emaciation. A possibility that deserves consideration is that the northwest cemetery burials could represent cases of special burial for persons who suffered from diseases considered particularly inauspicious. Such persons might have been judged not fit for cremation. Based on the vastu purusha mandala, one might venture an archeological prediction, namely that a cremation ground might be found outside the southwest corner of the Lothal settlement walls, near the bank of the now dry river that once ran there. The southern side of the vastu purusha mandala is ruled by Yama, the lord of death. The southwest corner specifically is occupied by Pitarah, the lord of the ancestors, or Nirritih, the lord of dying, exiting from life. This would make sense because the river flowed from north to south, and typically in Hindu towns, the riverside cremation grounds are usually located so that the river carries contaminated water away from the inhabited areas of the town.

Conclusion

In examining Lothal, a Harappan city in India, we see that it is laid out in a manner consistent with vastu principles. This city is from the 3rd millennium BCE. Vastu, which is mentioned in the Mahabharata, is considered a part of Vedic culture. So this would indicate that the city was part of the Vedic culture. It also suggests that the Mahabharata may be traced back to the same period of time.