Originally published by JAY CHESHES on NOV 23, 2015 in Town and Country Magazine

Henry Ford’s great-grandson was heading for ruin and then had a better idea: spiritual enlightenment. Now, 40 years later, Alfred Ford is spending millions to build a monument in India to the faith that brought him redemption.

Alfred Ford might have been any old corporate road warrior, in his pressed khakis and soft traveling shoes. He had come up from Calcutta, a three-hour drive along dusty roads clogged with mule-drawn carts, arriving in Mayapur, West Bengal, to look in on a big building project rising near a bend in the Ganges River.

In his VIP suite, across from the site, he slipped into a loose-fitting kurta and wraparound dhoti, a strand of beads creeping out from under his Indian shirt. A murmur of song began to rise in the distance. He caught the tune, barely moving his lips. “Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna, Krishna, Hare, Hare.”

For 40 years Ford has been repeating the mantra just as his guru instructed, 1,728 times daily, counting off under his breath while fingering beads tucked in a cloth bag around his neck. For all that time, Alfred Brush Ford—Motor City royalty, great-grandson of Henry, heir to a comfortable slice of his family’s $1.2 billion in Ford Motor stock—has been quietly living a double life. “I have kind of a split personality,” he says, “with one foot in one world and one in another.”

To his childhood friends in tony Grosse Pointe, Michigan, he’ll always be affluent, affable Alfie, who outlived his wild streak. But in faraway Mayapur—world headquarters of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON)—he goes by the name Ambarish.

His guru, A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, founded ISKCON, commonly known as the Hare Krishna movement, in an East Village storefront in New York in 1966, bringing his brand of Vaishnavism, a devotional branch of Hinduism that venerates Krishna (and is centered on the sacred Upanishad texts), to the lost souls of American youth. In 1975 he gave Ford his new name in an induction ceremony just outside Honolulu. While many friends shaved their heads back then, later dancing through airports in saffron robes to sell the guru’s books, Ford never abandoned his blue-blood identity. “I wasn’t expected to fully surrender,” he says.

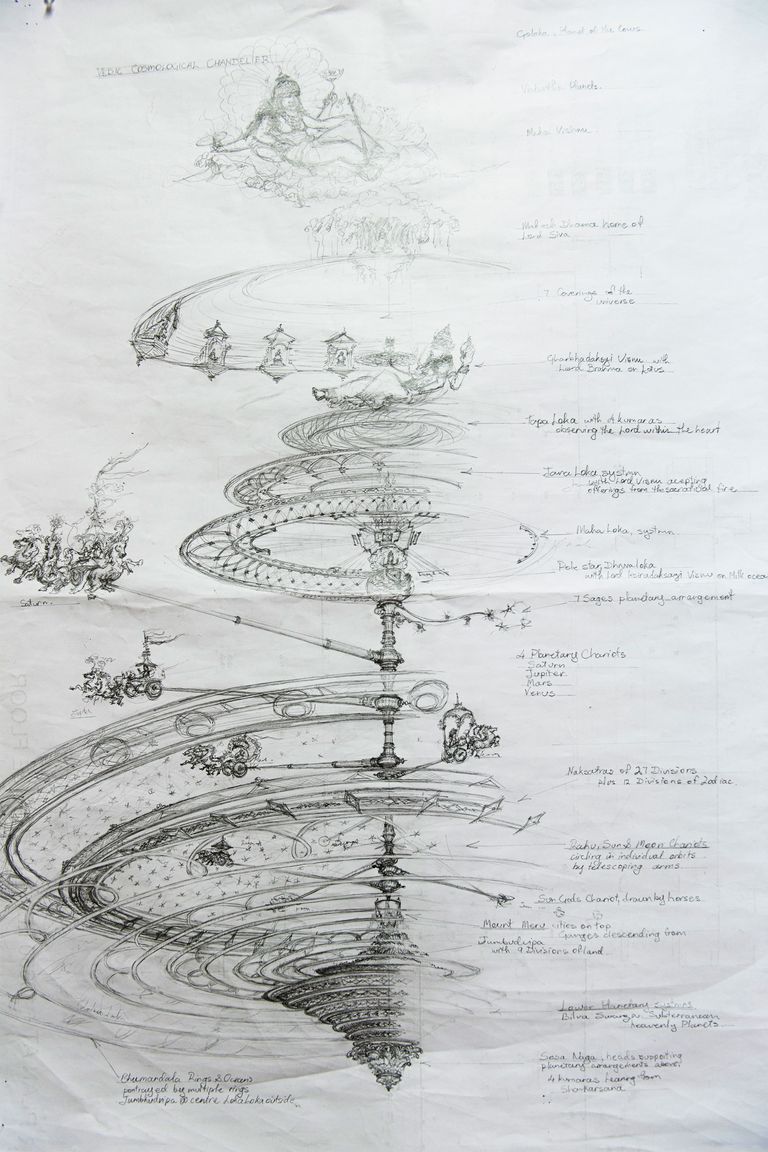

Prabhupada was a pragmatic leader and did what he could to coddle his deep-pocketed acolyte. The name he chose for Ford was that of an ancient king—”powerful, wealthy, devoted to Krishna. He served with his mind, his body, and his wealth,” according to Ford, who has followed that example, donating millions over the years to promoting Krishna Consciousness (the preferred shorthand name among the faithful) and funding temples, museums, and outreach centers. But the new project in Mayapur—the building of a spiritual San Simeon, a Hare Krishna Xanadu—is his real life’s work. The Temple of the Vedic Planetarium is the official name of the structure, an enormous marble edifice with a massive blue and gold dome on top. A cosmic chandelier inside depicts the universe as described in the Bhagavad Gita. It will be a monumental pillar of Alfred’s faith when it’s done, built partially with $25 million from his inherited fortune.

Up to 900 workers toil night and day on bamboo scaffolding, and the frame of the building already towers over this tiny Bengali village. Ford expects prayer to begin inside by 2020, and there is to be a grand opening that will draw international heads of state two years after that. Plans for an IMAX theater in a wing of the building, projecting Prabhupada’s life story, and a Las Vegas–style dancing fountain out front have recently been scrapped.

The 600,000-square-foot structure—bigger than St. Paul’s Cathedral or the Taj Mahal—is the first step in a long-term plan to turn the compound into a sort of spiritual Disneyland for the movement’s tens of millions of devotees worldwide; gardens, plazas, upscale condos, luxury hotel rooms, colleges, and even a retirement community are also planned. But Ford’s focus, for now, is on the temple.

His guru left detailed instructions for the building before he died, in 1977, hoping to draw Western converts by the thousands to Mayapur. It would take more than 30 years, and a lot of Ford’s money, for Prabhupada’s dream to begin taking physical shape. “I received enough instructions from him to keep me busy for the rest of my life,” Ford said as he strolled through the clamorous construction site.

A couple of times a year Ford makes the trek to Mayapur from his home in Gainesville, Florida—the center for one of the largest Hare Krishna communities outside India—to see what his seed money has delivered. On this trip he stopped first in South Africa, on a mission to raise the rest of the $90 million budgeted for the temple’s completion. “I gave what I could,” he says. “Now we want the rest of the world to chip in.”

At Hare Krishna events around Johannesburg he shilled for the temple’s “Square Foot” campaign, in which donors give $150 to subsidize a single square foot of the ongoing construction. “We raised $4 million,” he announced in Mayapur, at a meeting of the temple’s leadership team, a core group of once rudderless American hippies like Ford who joined the movement, as he did, in the 1960s and ’70s.

Yearning restlessly for answers—an iconoclast’s search for the meaning of life—seems to be a Ford family trait. Alfred’s first cousin Bill Jr., executive chairman of the Ford Motor Company, is a student of Buddhism who turns to meditation in times of crisis. “We do have a challenging, inquisitive mentality—that’s what Fords are,” Alfred says. Though both he and Bill Jr. were raised Episcopalian, each was drawn to Eastern ideas, as was their great-granddad. Henry Ford sampled religions like items in a buffet. He professed a lifelong belief in reincarnation and more than a hobbyist’s interest in Eastern spiritual thought. In 1926 the Detroit News reported on his meeting with a gray-bearded Sufi mystic. Those ideas didn’t stop Henry Ford from becoming one of the richest men in the world and one of America’s most divisive figures—a union buster and a pacifist with reactionary, anti-Semitic ideas.

“We didn’t really talk a lot about Henry growing up,” Alfred says. “He was kind of a distant legend.” Still, simply being a Ford in Detroit meant having the eyes of the city trained on your family at all times. “It was like being in a fishbowl,” he says.

Alfred’s mother Josephine was Henry Ford’s only granddaughter. His father Walter Buhl (“W.B.”) Ford II was descended from another venerable Ford family, the so-called “banking Fords,” also of Detroit but with no connection to the automobile industry, so the kids were actually “Ford-Fords.” W.B. ran his own industrial design firm and devised the modern Michelob bottle. “We became very familiar with it,” jokes Michael Glancy, a childhood friend of Alfred’s who is now a well-known glass artist.

Alfred was the youngest of four, with a much older brother and two sisters between them. They grew up in a big house in Grosse Pointe, near the rest of the Ford clan, with a full household staff and great works of art on the walls. “We had a big Picasso,” he says. “My father used to call it a portrait of my mother signing a check.” Winter vacations were spent at the family home in Hobe Sound, Florida, summers on the water in Seal Harbor, Maine.

Neither Alfred nor his siblings expressed much interest in the family business as kids, though cousins much higher up in the line of succession were, from an early age, groomed for leadership. For those not in line, as in many American dynasties, there was a fair share of wayward sons and daughters. Alfred’s cousin Benson Jr., probably the best known prodigal son, struggled with drugs, then declared war on the family in 1979, after his father’s death, hiring Roy Cohn to contest the will and demand a seat on the board. At one point he was caught with a hidden tape recorder at a family meeting, but he eventually reconciled and joined the family business.

In Detroit, Alfred hung with an overindulged crew of privileged kids (they called themselves the “In Crowd”), a closed circle of heirs (including Glancy, whose grandfather co-founded General Motors) who mostly dated within their ranks. Alfred attended high school at the Hill School, his dad’s alma mater, in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, and on weekends he’d slip off to New York to hit the boarding school bars on the Upper East Side. Boisterous and sometimes obnoxious when drunk, he was ejected from Café Carlyle for causing a ruckus during a Bobby Short show, and he almost got thrown out of Trader Vic’s for, as he recalls, getting so wasted he climbed into one of the war canoes on the wall, causing it to fall down.

When Alfred graduated, in the spring of 1968, his classmates nonetheless voted him most likely to succeed. “I told my parents, ‘That takes a lot of imagination,’ ” he says. “I already belonged to the Ford family. What else can you do? Stay alive?”

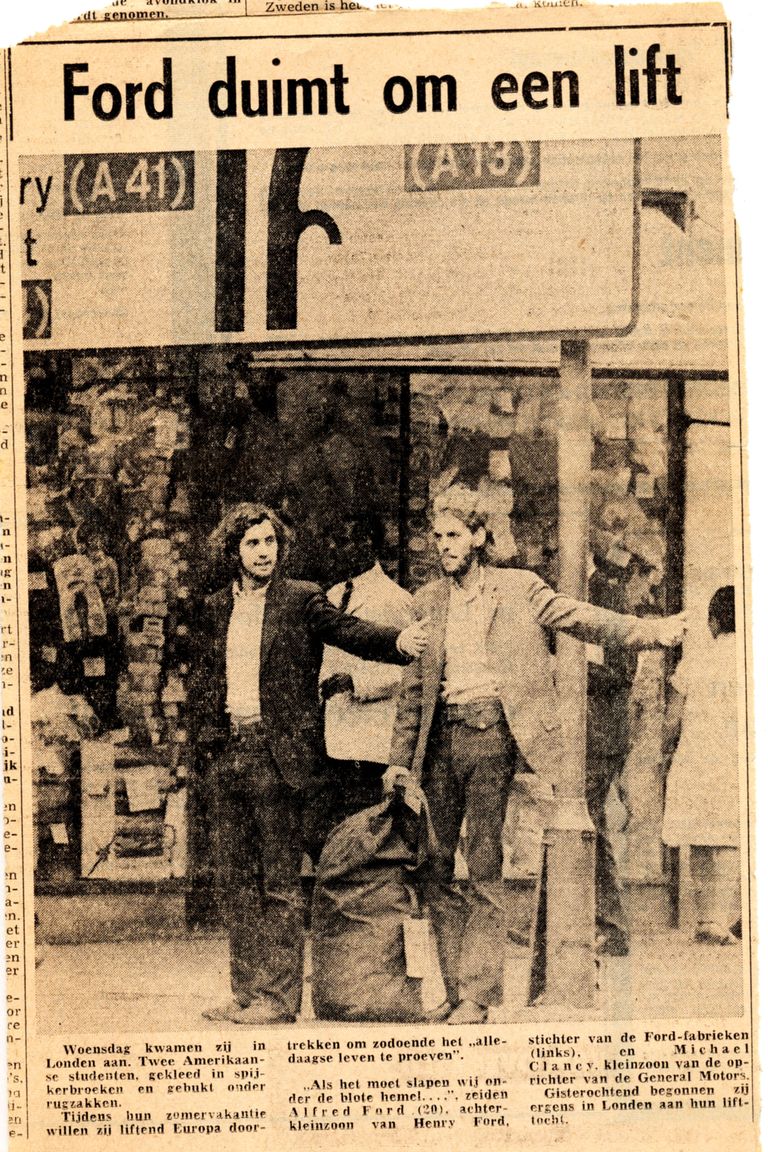

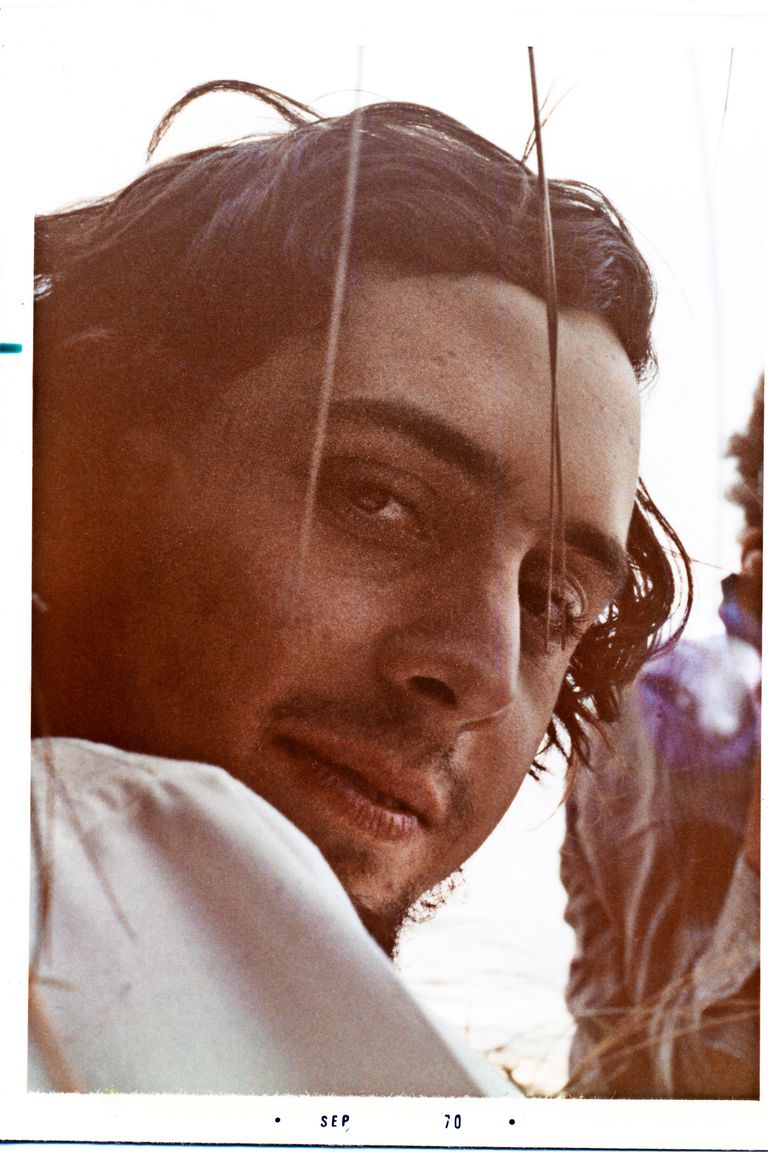

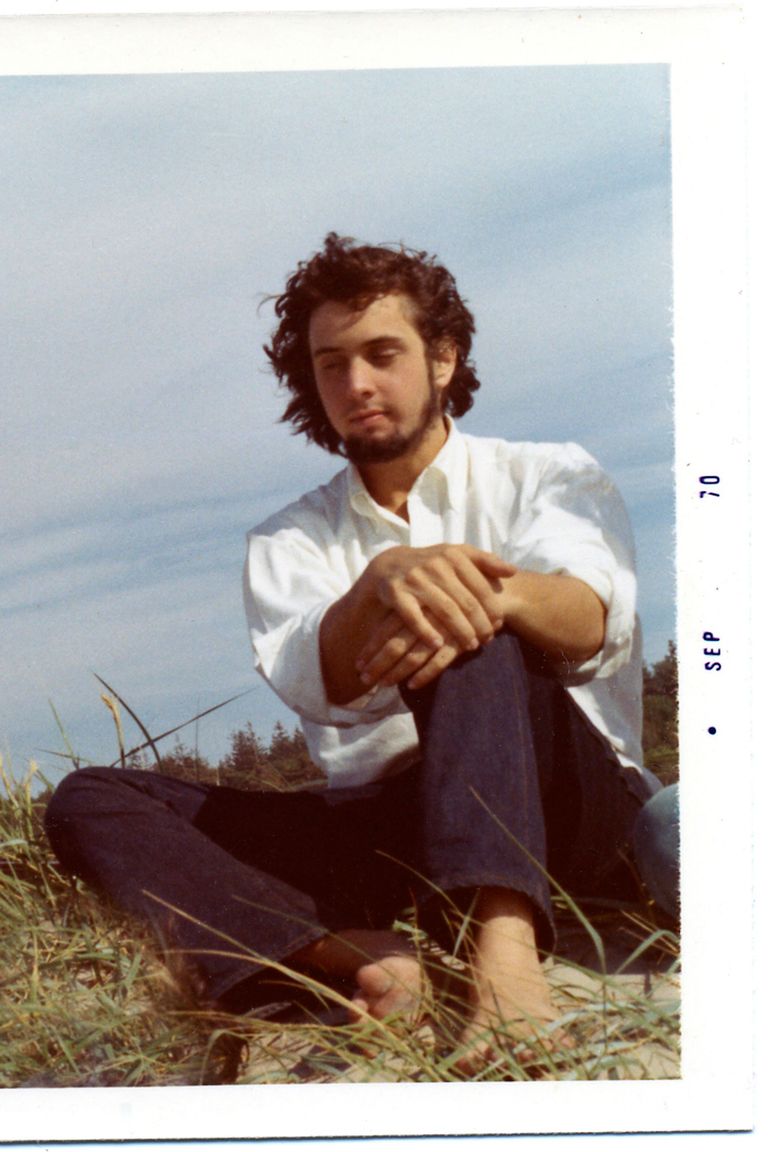

He then moved to New Orleans, to attend Tulane University, and jumped right into the counterculture, getting muddied at Woodstock and teargassed in DC during a march protesting the shootings at Kent State. In 1970 he traveled to Europe with Glancy, embarking for the summer on what the pair dubbed their “Ozone Tour,” which was pretty much what it sounds like. “Let’s just say we did inhale,” says Glancy. As a belated high school graduation gift, their parents had booked them passage on the QE2. When they got to London, the tabloid press was waiting to pounce on the American heirs. “A newspaper flashed the headline, ‘GM and Ford merge for tourism,’ ” Glancy recalls. “It showed a hippie Alfred and me in beards and long hair, hitchhiking, and it talked about how we had gobs of money sewn into our blue jeans.” The high-flying vagabonds met up with other friends and drove across the continent in a Ford station wagon, catching Pink Floyd’s show in St.Tropez.

Two years later Alfred dropped out of college—just a few physed credits shy of an art history degree—and moved out to Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Though he had taken up yoga and meditation at Tulane, doing his best to clean up, he had begun to realize that alcohol was becoming a serious problem. “It got really bad,” he says, “driving and drinking, and blacking out.” His older brother Buhl had battled alcoholism as well. “I didn’t understand that it’s a disease,” Ford says. “I thought I could handle it on my own.”

While he was out west grappling with sobriety, a friend from Detroit came to visit, bringing books and beads. He explained that he had found Krishna Consciousness. Ford was intrigued. “Like many of us back then, I couldn’t identify with my parents, was definitely searching for something new,” says Ford, who, in the tradition of Larry Darrell, the Midwestern heir who finds enlightenment in India in Somerset Maugham’s 1943 masterpiece The Razor’s Edge, sought a spiritual escape from the burdens of his birthright.

The Hare Krishnas share with Jews, Christians, and Muslims a devotion to a single omniscient being, embodied for them by Lord Krishna. Piety in this life, they believe, will bring good karma in the next, the ultimate goal being to eventually reach Krishna’s plane. “The message that really resonated with me is that God is a personality, the supreme personality,” Ford says. “That we have an eternal relationship with him.”

In 1973, after immersing himself in Prabhupada’s works, Ford flew to Dallas—home to the country’s first gurukula, or Hare Krishna school—to meet the author. “He was a really wonderful person, very human but extremely self-realized, a pure devotee. He said, ‘You’re Henry Ford’s great-grandson?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ He said, ‘Well, where is he now?’ It put everything on a very spiritual level.”

The Hare Krishna movement, born in the U.S., had real momentum by then, spurred by a general interest in Indian culture—tied, in that period, to psychedelic music and drugs —as well as by celebrity dabblers such as George Harrison (“My Sweet Lord” is a Hare Krishna song), Peter Sellers, and Allen Ginsberg. For Ford, however, it was much more than a fad. Though he continued to struggle with alcohol, he found the Hare Krishna life, which stresses community, purpose, and structure, hard to resist. He was drawn to both the discipline and the sacrifice, including the rigorous program of chanting and the strict vegetarian diet.

Prabhupada invited Ford to Hawaii. The guru had been spending a lot of time on Oahu, meditating and translating spiritual texts into English. While touring the small Honolulu temple, which the Hare Krishnas had already outgrown, the guru asked him for financial help. “My parents weren’t terribly happy about it,” Ford says of the $600,000 he contributed toward the purchase of a larger building. “My father said, ‘Why don’t you buy something a little less expensive next time?’ ”

Within a year of meeting Prabhupada, Alfred was officially initiated into the Hare Krishna movement, at the new temple in Hawaii. His family—along with the rest of the country—learned of his devotion to Krishna while watching the Today show one morning in 1975. “The press in India had published an article saying I was giving up all my wealth and moving to India, and the American press picked it up,” Ford says. “My sister told me she almost passed out in her breakfast.”

Prabhupada clearly saw financial promise in Ford. All across the U.S., growing Hare Krishna communities were in need of more space. The guru asked his new acolyte to focus his energies on his hometown, Detroit. The temple president there had found a beautiful but seriously decayed Mediterranean-style stucco mansion— auto magnate Lawrence Fisher’s former home—in a once grand neighborhood. Prabhupada asked Ford to buy it and make it a showplace for Krishna Consciousness. “I was a little apprehensive,” Ford says. “But Prabhupada said, ‘Bring Krishna here and the whole neighborhood will improve.’ ”

Prabhupada saw something else in Alfred: a publicity tool, and he had a clever PR stunt in mind. Elizabeth Reuther, daughter of United Auto Workers president Walter Reuther, had become a devotee in 1972, after both her parents died in a plane crash. The two families had historically been on opposite sides in the labor wars; Reuther’s father was once beaten by Henry Ford’s hired thugs. Wouldn’t it be something, the guru reasoned, if they came together to build the new Detroit temple? So he asked Reuther to chip in too. She gave her entire inheritance, a $500,000 life insurance settlement. Ford picked up the rest of the tab, about $2 million. “I’m so grateful I gave everything,” says Reuther, who is still a believer, “because it gave me a strong spiritual foundation.”

In the spring of 1977, with work on the Fisher mansion just starting, Prabhupada died, at 81, and the movement he started soon fell into chaos. He left behind 11 successors, Western gurus he had authorized to initiate converts. Infighting, defections, and serious abuses of power followed. The incidents of sexual assault, grand larceny, drug trafficking, Waco-style weapon stockpiling—even murder—could have filled a 450-page book, and did: John Hubner and Lindsey Gruson’s 1988 exposé, Monkey on a Stick. The worst mayhem occurred in 1979, at a rural community in West Virginia where a rogue guru opened his own lavish “Palace of Gold.” By the early ’80s another guru, a proponent of LSD, had started sowing disorder in the Detroit temple. Ford became so disillusioned he fled to a splinter group in San Francisco for the next few years. The Hare Krishna Governing Body Commission dispatched Prabhupada’s former personal servant— a New Yorker named Charles Bacis—to bring Ford, and his checkbook, back into the fold. “I was told to take care of Ambarish,” says Bacis, who is now an elder statesman who goes by the name Bhavananda. “It was decided I would be the best one to do it because I have a certain sophistication.”

Bacis, a once promising filmmaker and actor who had been a regular at Andy Warhol’s Factory (he was in Ciao Manhattan with Edie Sedgwick), joined the movement in 1969, leaving his glamorous It boy life behind. Like many early converts, he had been on a drug-fueled downward spiral before finding Krishna Consciousness. “I was supposed to start work as Otto Preminger’s assistant on a Monday,” he recalls. “The day before, it was pouring rain. I drove a group to the temple at 26 Second Avenue in my red Porsche, for the vegetarian feast. And I just stayed. It was a spontaneous thing. When I finally met Prabhupada I had this immediate impulse that I wanted to serve him.”

Bacis eventually rose to become the Hare Krishnas’ unofficial celebrity handler, a charismatic, erudite liaison for notables like Annie Lennox and Boy George. When he found Ford, Bacis was able to lure him back from San Francisco, first to Detroit, where the two men worked to salvage the Fisher mansion project, and then to Australia. It was there, at the Hare Krishna compound on the edge of Sydney, that Alfred met his future wife, Sharmila Bhattacharya, a Bengali Brahmin (and Ph.D. student in biochemistry) whose father had been trying to marry her off to another man.

“I thought all Americans were brash and arrogant,” she says. “Alfred was so sweet, it kind of melted my heart.” They dated via letters and phone calls, marrying a year later.

“The Ford name won out,” says Bacis, who introduced the two during a ceremonial feast. “In her astrological chart it said she was going to marry a millionaire.”

Back in Detroit, Ford finished restoring the Fisher mansion, now known as the Bhaktivedanta Cultural Center, for its grand reopening. On that day, May 25, 1983, with Ford’s parents watching, the mayor of Detroit gave Ford a civic award. The building was a magnificent showcase for a religious movement struggling with some significant demons. “We used all first class materials,” Ford says. “There were Scalamandré curtains, fountains, beautiful gardens.” Inside, there were great works of Indian art that Ford had collected for a short-lived gallery he had once run. Peacocks wandered the grounds, and their sometimes blood-curdling shrieks provoked rumors that children were being tortured inside (which seems like a foreshadowing of the child abuse lawsuit the Hare Krishnas would settle years later). Still, the house became a tourist destination for a while. “It was part of the Auto Baron Tour,” Ford says, “with Fair Lane, which is Henry Ford’s house; my grandmother’s house; and the Dodge estate, Meadow Brook.” Of course, the Fisher mansion was just the warm-up act.

“We want this building to last 1,000 years,” Ford says of the Mayapur temple. We’re having lunch—an all-you-can-eat Indian spread—in a VIP dining room across from the construction site. Deprivation may be at the core of Hare Krishna practice—even Ford went through a brief period of sleeping on floors and taking cold showers—but good food is one pleasure that’s officially sanctioned. Evenings here are generally spent in the compound’s alfresco pizzeria, a seasonal pop-up run by an Italian devotee who makes top-notch Neapolitan pies with his own fresh mozzarella. Most nights Ford is in bed by eight, then up again at 3 a.m. to begin morning chants.

Alfred Ford may be the ideal ambassador for where the movement is heading, a well-spoken family man who can easily blend into mainstream American society. He has two grown daughters with Sharmila, and neither is a Hare Krishna devotee or a trust fund train wreck. The younger one, Anisha, is in her senior year at the University of Chicago; she interned at the Ford Motor Company last summer and volunteers at inner city schools. Her sister Amrita is married to a Harvard-trained attorney, Hrishikesh Hari, and hopes to pursue a Ph.D. in the medical field, as her mother did.

Ford insists Prabhupada got him started on the path to redemption. “It’s a fairly simple story: Bad boy meets saintly person, becomes a new person,” he says. “I wouldn’t be alive today the way I was going.” But almost as much as his faith, Ford credits marriage and children, as well as regular AA meetings, with bringing his addiction to ground and his life together at last. “Alfred’s parents weren’t very happy when he joined the Hare Krishnas,” Sharmila says. “After we got married, they saw how we lived, and they were very impressed.”

Apart from sitting on the board of the Ford Motor Company Fund, Ford has mostly kept out of the family business, focusing, with limited success, on his own startups—investments in a string of failed ventures, including a wealth management website for high-net-worth families and a Himalayan ski resort that never got off the ground. And though there is still a small biotech firm that he’s funding, the Temple of the Vedic Planetarium is his main focus, a big, bright symbol of the Hare Krishna movement’s evolution from a fringe group with cultish overtones to a more established religion.

“When we were first married, Alfred showed me all the letters Prabhupada had written with specific instructions on building this temple,” Sharmila says. “He had a definite vision. He thought it would bring the whole world together in a way the United Nations had not.”

Ford hopes it will at least announce to the world that Krishna Consciousness has finally arrived. “The temple is bigger than I thought it would be,” he says. “It’s the kind of statement, for our world, that we wanted to make.”